The following is the introduction to author Kristian Williams’ new book, Between the Bullet the Lie: Essays on Orwell, recently published by AK Press.

George Orwell, like Rudyard Kipling, is one of those writers whom one quotes without meaning to.(1) “Cold War,” for example, was his coinage, albeit without the capitals.(2) So were the more commonly recognized “Big Brother” and “Thought Police”—both from 1984, a number that continues to signal a dystopian future more than thirty years after the date has passed.(3) “Orwellian” is of course used to signify the very things the writer warned against—as is sometimes, less forgivably, simply “Orwell.”

Orwell remains a recognizable figure—even if there is some confusion about what he was a figure of.(4) I remember before the 2004 election seeing ironic, ill-conceived “Bush/Orwell” bumper stickers, intended to compare the reigning administration with the fictitious totalitarian regime of 1984. A friend of mine suggested that “Bush/ O’Brien” would be more accurate, which is true though far fewer people would recognize the name of the novel’s Inner Party inquisitor.(5) “Bush/Big Brother,” in contrast, would border on the too-obvious-for-humor. “Big Brother,” as a term, has in some ways outgrown its literary origins and become simply an everyday phrase—not to mention a popular television show about the joys of voyeurism and control in an artificial environment entirely lacking privacy.

Now, as we drift through the second decade of the seemingly permanent War on Terror, Orwell’s place in the political lexicon is if anything more secure—especially in connection to ubiquitous surveillance. In 2011, United States Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer worried that warrantless GPS-tracking could “suddenly produce what sounds like 1984.”(6) And two years after that, when Edward Snowden revealed the true range of the National Security Agency’s electronic surveillance programs, online sales of 1984 shot up 3,000 per cent in just a few days.(7) The book hit the best-seller lists again in 2017, after an advisor to President Trump characterized the administration’s blatant falsehoods as “alternative facts.”(8) Meanwhile, two hundred theatres nationwide responded with simultaneous screenings of the film version of 1984.(9) It is remarkable that any writer might maintain such currency nearly seventy years after his death. It is more astonishing still for a writer whose work so specifically addressed the affairs of his time.

Orwell’s work—most obviously his journalism, but almost equally his novels—supplies a kind of running commentary on world events unfolding during the period of his writing. The Thirties and Forties supplied the atmosphere of his fiction and nonfiction alike, even when current events did not directly dictate the subject matter. The preoccupations of the age—socialism, fascism, poverty, war—worked their way into every crevice, and colored every phrase: “Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936,” Orwell explained, “has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic Socialism, as I understand it.”(10) Essays on subjects as remote as comic postcards or Jonathan Swift follow an arc drawn by the gravitational force of these most central concerns. Much of Orwell’s work retains a historical interest, less for the facts it records (those are available elsewhere) than for his vivid portrayal of what things were like. His work helps us to understand the Depression, for instance, in The Road to Wigan Pier and essays like “The Spike,” not merely through the enumeration of government policies and economists’ statistics, but in descriptions of the homes of unemployed miners and the prison-like shelters offered to tramps in the name of Christian charity. In Burmese Days, the corruption of the Empire is revealed in the depiction of a provincial controversy and the moral ruin of an insignificant timber merchant. The long moment of dread before the inevitable World War is voiced in Coming Up for Air, not by newspaper editors or parliamentarians, but by an overweight insurance salesman who only wants to go fishing. The worm’s eye view, Orwell thought, can be as revealing as the eagle’s.(11)

Orwell’s approach was characteristically that of an engaged outsider. He did not try to speak for the Burmese peasants, or the Wigan miners, or the revolutionaries in Spain. He did not even pretend that he could always sympathize with their feelings, agree with their views, or approve of their habits. What he did do, however, was to go where such people were and record what he found there.

He did not cast himself as a neutral observer; he was a partisan and sometimes a participant. Yet he was not at home amid the events, or among the people, he so carefully described. It was a source of some frustration for Orwell that the miners at Wigan, among whom he lived for weeks, could never regard him as precisely an equal, and that “it needed tactful maneuverings to prevent them from calling me ‘sir.’”(12) Later, writing in Homage to Catalonia, recalling Barcelona suddenly immersed in revolution—the buildings “draped with red flags,” walls “scrawled with the hammer and sickle,” “loudspeakers … bellowing revolutionary songs”—Orwell commented first on the very strangeness of it: “All this was queer and moving. There was much in it that I did not understand, in some ways I did not even like it, but I recognized it immediately as a state of affairs worth fighting for.”(13) Fight he did do, and as his reward he was shot through the throat by a fascist sniper, forced to flee the Communist secret police, and alternately ignored and libeled by the socialist press in England. The ordeal only strengthened his resolve. It solidified both his belief in socialism and his independence of mind.(14) His critical distance did nothing to diminish his moral commitment; nor vice versa. Orwell proved himself willing to fight, to die if necessary, but he would not cease probing, questioning, judging by his own standards. He was ready to follow orders, but not to swallow absurdities.(15)

Like his protagonists George Bowling, Gordon Comstock, and Winston Smith, Orwell felt himself out of place in the modern world. He nurtured a fantasy of a quiet life in “a peaceful age,” writing “ornate or merely descriptive books,”(16) untroubled by politics and war. “A happy vicar I might have been, Two hundred years ago,” he begins one poem; it concludes: “I wasn’t born for an age like this: Was Smith? Was Jones? Were you?”(17) Though Orwell wrote of the events of his time, though he did his best to take part and to shape them, he was not, by character or disposition, a figure of his time. His friend, the anarchist writer George Woodcock called him a “nineteenth-century liberal.”(18) Another friend, Cyril Connolly, described him as “a revolutionary in love with 1910.”(19) As Orwell readily acknowledged, the world that seemed his own was one that no longer existed—a world with warm beer and horse carts, and no V-1 rockets crashing into London.(20)

It is precisely this old-fashioned quality that accounts for his endurance as a cultural figure. Just as a conservative suit will age better than a flashy one, Orwell’s preference for plain-speaking over artistic experimentation, common sense over high theory, and common decency over fashionable cynicism has made him one of the twentieth-century writers who remains not only readable but worth reading.

That this conservative disposition would align with radical politics is exceptional and interesting, but by no means a contradiction. As I will argue, Orwell’s radicalism developed as an extension of these traditional values, and these values helped to ground his politics in messy, discomforting, unreasonable reality, rather than in cozy fantasies, too-neat propaganda points, or Marxian scholasticism. As a consequence, he has come to represent intellectual honesty rather than intellectual depth. That assessment relies on a misunderstanding, and one with which he himself was complicit.

Orwell is not renowned as a deep thinker, partly because deep thinking has become confused with difficult writing—that is to say, with writing that is difficult to read. It is in fact harder to produce smooth, clear prose, but readers are prone to assume that if they do not struggle over a passage then the writer must not have either. They are just as likely to suppose—or a certain type of reader is, anyway— that if a piece of writing is obscure it is also necessarily profound. (This premise can be readily disproved by referring to any document produced by the Internal Revenue Service.) Furthermore, if it is a struggle to interpret some piece of dense and challenging prose, then when one arrives at the meaning one is liable to find oneself persuaded just by virtue of having put in the work to decipher it. The reader becomes invested in the ideas by confusing a hard-earned understanding of the text with an important discovery about the world. A great many theorists have thus built towering reputations on foundations of fog.

Orwell, of course, took the opposite approach. He labored to make the written word sound as natural as the spoken. He wanted his prose to be “like a window pane”—so transparent, one forgets that it is there.(21) That too is a trick, however. One looks through the glass, not at it, and thus one forgets that the window frames and colors what one sees. Additionally, Orwell liked to issue shocking, startling, outrageous pronouncements, but with a tone suggesting that they must be obvious to anyone with the courage to admit it. Sometimes they are obvious, if only after they’ve been pointed out to us. Other times, however, they are simply baffling. “Why on earth would he say that?” we wonder. And his style, at once casual and dramatic—like that of a stage magician who refuses to be impressed by his own trick—hides the mental work that went into forming his conclusions.

Many of my essays here began with just such a moment of puzzlement. I would come across a line—for example, “you do less harm by dropping bombs on people than by calling them ‘Huns’”—and my brow would crease.(22) My first thought is, of course, that that cannot possibly be right. I would re-read the sentence to see if a word had perhaps been omitted by mistake. And then I would start to wonder why he would say such a thing. I’d look for similar statements, related observations, common themes. Beginning with the points visible at the surface, it is sometimes possible to excavate the arguments connecting them. In Orwell’s work, these arguments often proceed in stages, spread across several publications, sometimes separated by years.

This collection, resulting from such investigations, is highly idiosyncratic. The agenda throughout is wholly my own. The questions I have tried to answer and the issues I seek to address are taken up here simply because I find them interesting and important. Roughly the first half of the book is occupied with my efforts to understand various aspects of Orwell’s outlook—his ethics, his patriotism, his emotional life. The second half attempts to apply his thought to a range of political (and to a lesser degree, literary) questions that trouble us today.(23) My aim has not been to treat him as an oracle issuing sacred decrees, but instead to see how his thought can help us to understand the circumstances in which we find ourselves.(24) In other words, the question I pose is not what he would say, given present conditions, but how we might use what he did say. Naturally my perspective is in some important respects very different from Orwell’s own, and both the subjects I address and the conclusions I draw necessarily reflect these differences. I am writing more than half a century after his death, from the US rather than the UK, and I approach politics as an anarchist with social-democratic sympathies, rather than as a democratic socialist with anarchist sympathies.

Furthermore, much of my work here reads against the grain of the text, or at least, against the usual interpretations—for instance, by emphasizing the aestheticist element of Orwell’s thought, or detecting an optimistic note in both Homage to Catalonia and 1984. And in the process, I relate Orwell to a surprising range of other figures— CrimethInc and Camus, Wilde and Dickens, Henry Miller and James Burnham, Charlie Chaplin and Nietzsche.

I should stress that I am particularly interested with what Orwell consciously thought, not with his deepest psychological drives and motives. And I am only really concerned with what he did to the degree that it might illuminate his thinking. Thus this collection is in no sense a biography, though it does at points make use of biographical materials. I likewise deal only sparingly with the critical literature on Orwell, citing it when it has informed my reading but not engaging the arguments directly. My chief source, therefore, is the body of Orwell’s published work. As Orwell said of his own essay on Dickens, “I have never really ‘studied’ him, merely read and enjoyed him, and I dare say there are works of his I have never read.”(25)

I take it for granted that the reader will have some familiarity with Orwell’s writing, though I do not expect her to be any sort of expert. I have tried to provide sufficient context for the bits that I quote, but except where it is necessary to make some definite point, I have also sought to spare the reader the tedium of paraphrase. At the same time, I have done my best to make my meaning clear without demanding lengthy study beforehand.(26) Most of these essays were not written for this book, nor even with the thought that they would eventually appear together. The resulting collection is necessarily a bit fragmentary. I have made no effort to be comprehensive—to recount all the major events of Orwell’s life, or to carefully dissect every book—and there is no single, unifying argument. But the essays do fit together, I think, connected by some common themes that recur throughout and even develop as the volume progresses. Among them are: the relationship between aesthetics, ethics, and politics; the difference between honesty and integrity; the role of courage in the face of defeat; the corruption of language; the importance of observation and evidence; and the shortcomings of the Left.

On the last point, we should remember that, despite his criticisms of the Socialist movement, Orwell felt that he “belong[ed] to the Left and must work inside it.”(27) His criticisms were intended, not to undermine the Left but to strengthen it, not to stifle its progress but to preserve its ideals and to advance its cause. It is in that same spirit, in these essays, that I voice criticisms of my own, and my harshest words are generally reserved for those with whom I sympathize most fully. One can examine an enemy’s follies somewhat clinically, or with an ironic distance, but the errors and inequities of one’s own side weigh on the mind more urgently and insistently.

Orwell remains useful to us now—and by “us,” I mean especially the anti-capitalist Left—because what we most desperately need is to bring radical ideas into touch with reality. That is true in two respects: The problems facing our world—climate change, inequality, permanent war—are very serious and will surely not be solved through minor adjustments in policy. They require solutions commensurate to the danger, changes fundamental to society. Equally, it is absolutely imperative that radical ideas address the world as it actually exists, as we find it in our lives rather than in our daydreams or our theories.

Many of Orwell’s observations and especially his criticisms— whether of the cruelty of imperialism, the vulgarity of capitalism, or the inanities of the Left opposition—maintain their force and still hit their targets. And yet, what he tells us about politics, culture, and mid-century England may ultimately be less important than his approach, even his style. His reverence for fact, his sense of decency, his respect for intelligence, his faith in the common people, his courage (moral, intellectual, and physical), and his refusal to mock traditional virtues for the sake of looking sophisticated—these are qualities disastrously lacking in our present discourse—political and cultural, Left and Right, popular and intellectual. What we have instead is a culture of self-satisfied sadism, of ratings-driven pseudo-controversy, of talking points in place of facts, of smug cynicism and slavish conformity, of dismissal instead of critique, and of disdain for anyone who isn’t exactly as glib and soul-dead as we are ourselves.(28)

The Left is as bad as the Right, in this regard. “Particularly on the Left,” as Orwell so incisively put it, “political thought is a sort of masturbation fantasy in which the world of facts hardly matters.”(29) What is most striking are the lengths to which alleged radicals will go to preserve their narcissistic feelings of superiority—preaching a gospel that they believe, with one part of their minds, to be unrealizable, thus preserving their outsider status, the freedom of irresponsibility, and a sense of ideological purity, while also believing with a different part of their minds that the ideals they espouse are, miraculously, embodied in their own actions and manifest in their own lives. The result is a Left that somehow manages to simultaneously take itself far too seriously and never seriously enough. The petty dramas, the sectarian bickering, the insular “scenes,” and ineffectual “actions” are all elevated to crucial, symbolic, epoch-defining, world-historical heights, while at the same time invoking, but never really coming to grips with, the scale of the challenges before us—including the possibility, and perhaps likelihood, of human extinction. For too long the Left has sought to preserve its idealism by mentally fleeing any possible doubts or objections. In the short term, such a strategy may preserve any number of outdated, contradictory, or merely ridiculous orthodoxies, much as certain chemical elements can only exist inside a laboratory; but in the long term the attempt to avoid challenges to one’s own assumptions, testing our ideas against experience, and revising our theories in light of new information can only prove self- defeating.(30) As Orwell warned, “sooner or later a false belief bumps up against solid reality, usually on a battlefield.”(31)

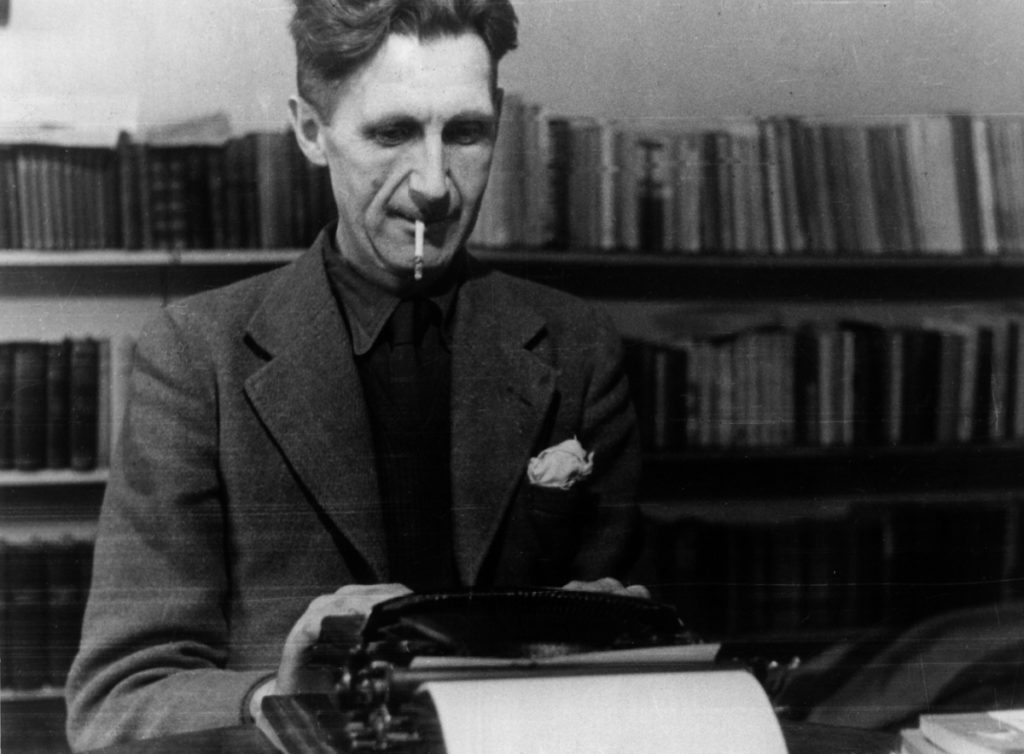

Orwell’s work, I believe, models another approach. More important, even, than his ideas is his example in handling these ideas—the clarity of expression, the resistance to dogmatism, the “power of facing unpleasant facts.”(32) And further back, behind that approach, there stands Orwell himself, who ought not be revered as any kind of saint, but who may instead serve as an example of a flawed, often unhappy individual, doing his best to preserve his integrity and nudge the world, however slightly, toward a more sane and decent future.

Kristian Williams is the author of Our Enemies in Blue: Police and Power in America, American Methods: Torture and the Logic of Domination, and Between the Bullet and the Lie: Essays on Orwell. He is presently at work on a book about Oscar Wilde and anarchism.

Notes:

- George Orwell, “Rudyard Kipling,” in The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell, Volume II: My Country Right or Left, 1940–1943, eds. Sonia Orwell and Ian Angus (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1968), 192–93.

- George Orwell, “You and the Atom Bomb,” in The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell, Volume IV: In Front of Your Nose, 1945–1950, eds. Sonia Orwell and Ian Angus (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1968), 9. Confirmed as first use by Oxford English Dictionary, OED.com, accessed September 17, 2016.

- I realize that, properly speaking, the title should be rendered Nineteen EightyFour. But the Signet paperback that I bought in high school, and have read and reread since then, has it as 1984. Then again, that is the same edition that advertises itself as containing a “Special Preface” by Walter Cronkite—but does not. George Orwell, 1984 (New York: Signet, 1984).

- For an examination on the competing, conflicting, contradictory uses of Orwell as a figure, see: John Rodden, The Politics of Literary Reputation: The Making and Claiming of “St. George” Orwell (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989).

- Josef Schneider, in conversation, 2004.

- Quoted in Sarah Peters, “Justice Breyer Warns of Orwellian Government,” The Hill, November 8, 2011, thehill.com/blogs/blog-briefing-room/news/ 192445-justice-breyer-warns-of-orwellian-government, accessed September 2, 2016.

- Alana Abramson, “Sales of Orwell’s 1984 Increase as Details of NSA Scandal Emerge,” ABC News, June 11, 2013, http://abcnews.go.com/blogs/headlines/ 2013/06/sales-of-orwells-1984-increase-as-details-of-nsa-scandal-emerge/, accessed September 2, 2016.

- Kimiko de Freytas-Tamura, “George Orwell’s 1984 is Suddenly a Best-Seller,” The New York Times, January 25, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/25/books/1984-george-orwell-donald-trump.html?_r=3, accessed may 2, 2017.

- Delaney Strunk, “Theaters are Screening 1984 to Protest Trump,” CNN.com, April 4, 2017, http://www.cnn.com/2017/04/04/us/1984-theater-protest-trnd/, accessed May 2, 2017.

- George Orwell, “Why I Write,” in The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell, Volume I: An Age Like This, 1920–1940, eds. Sonia Orwell and Ian Angus (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1968), 5. Emphasis in original.

- Orwell put this observation in negative terms, suggesting that “a bird’s eye view is as distorted as a worm’s eye view.” George Orwell, “War-Time Diary: 14 March 1942–15 November 1942,” in Collected, Vol. II, 430. Ellipses in original.

- He explains: “For some months I lived entirely in coal-miners’ houses. I ate my meals with the family, I washed at the kitchen sink, I shared bedrooms with miners, drank beer with them, played darts with them, talked to them by the hour together. But though I was among them, and I hope and trust they did not find me a nuisance, I was not one of them, and they knew it even better than I did. However much you like them, however interesting you find their conversation, there is always that accursed itch of class-difference, like the pea under the princess’s mattress. It is not a question of dislike or distaste, only of difference, but it is enough to make real intimacy impossible. Even with miners who described themselves as Communists I found that it needed tactful maneuverings to prevent them from calling me ‘sir’; and all of them, except in moments of great animation, softened their northern accents for my benefit. I liked them and hoped they liked me; but I went among them as a foreigner, and both of us were aware of it.” George Orwell, The Road to Wigan Pier (San Diego: Harcourt, 1958), 156.

- George Orwell, Homage to Catalonia (San Diego: Harcourt Brace and Company, 1952), 4–5.

- Orwell wrote to Cyril Connolly from Barcelona, “I have seen wonderful things & at last really believe in Socialism, which I never did before.… On the whole, though I am sorry not to have seen Madrid, I am glad to have been on a comparatively little-known front among Anarchists & Poum people instead of in the International Brigade, as I should have been if I had come here with CP credentials instead of ILP ones.” Orwell, “Letter to Cyril Connolly (June 8, 1937),” in Collected, Vol. I, 269.

- Orwell, “Writers and Leviathan,” in Collected, Vol. IV, 412–13.

- Orwell, “Why I Write,” in Collected, Vol. I, 4.

- Ibid., 4–5.

- George Woodcock, “George Orwell, 19th Century Liberal,” in George Orwell: The Critical Heritage, ed. Jeffrey Meyers (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1975), 235.

- Quoted in Rodden, The Politics of Literary Reputation, 91.

- That is the main theme of his novel Coming up for Air (London: Secker & Warburg, 1963).

- Orwell, “Why I Write,” in Collected, Vol. I, 7.

- George Orwell, “As I Please (August 4, 1944),” in The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell, Volume III: As I Please, 1943–1945, eds. Sonia Orwell and Ian Angus (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1968), 199.

- That should not be confused with any effort to bring Orwell “up to date.” As a writer he belonged to his time as definitely as he belonged to his native language. Nor is it an attempt to “claim” Orwell for any ideological camp, or to defend him from his various critics and detractors. Christopher Hitchens already wasted too much ink defending Orwell’s honor from insults which otherwise may well have been forgotten. And who, we may ask, will save Orwell form Hitchens? Christopher Hitchens, Why Orwell Matters (New York: Basic Books, 2002).

- John Rodden is right to insist that “questions about a man’s posthumous politics are manifestly absurd,” and his study assembles the evidence that illustrates the point. Rodden, The Politics of Literary Reputation, 263.

- George Orwell, “Letter to Humphrey House (April 11, 1940),” in Collected, Vol. I, 131.

- For those so inclined, however, a study guide is included as an appendix.

- George Orwell, “Letter to the Duchess of Atholl (November 15, 1945),” in Collected, Vol. IV, 30.

- The difference between critique and dismissal was brought to my attention by Kevin Van Meter, in conversation, 2016. He makes a related set of points in: Kevin Van Meter, “Freely Disassociating: Three Stories on Contemporary Radical Movements,” Institute for Anarchist Studies, June 8, 2015, https://anarchist studies.org/2015/06/08/freely-disassociating-three-stories-on-contemporary -radical-movements-by-kevin-van-meter/, accessed September 30, 2016.

- George Orwell, “London Letter to Partisan Review (December 1944),” in Collected, Vol. III, 295.

- It will be observed, here and in the essays that follow, that in my criticisms of the Left I generally omit specific examples. The reasons for this choice are two: First, the problems I point to are long-standing, but fashions change very quickly. Any example I offer, therefore, will likely seem dated inside of two years and the fact that the particular example may have expired ought not to mislead us to conclude that the problem has been overcome. Second, the failings I discuss are so common that even a representative sample of recent instances would quickly prove tiresome, but the selection of one or two must be arbitrary and may seem like I am singling out specific individuals or groups while sparing others. In general, then—with the exception of my direct response to CrimethInc—I have foregone direct quotation or the citing of specific cases. I trust that anyone passingly familiar with contemporary left-wing politics will recognize the problems as I describe them.

- George Orwell, “In Front of Your Nose,” in Collected, Vol. IV, 124.

- Orwell, “Why I Write,” in Collected, Vol. I, 1.